Law-Splainer - Part 2: Structure of the Federal Courts

In Part 1 of our Law-Splainer series, we covered what it takes to file a federal lawsuit and a number of factors that need to be considered before filing a complaint in a federal district court. In this part, we’ll discuss the structure of the federal court system.

A Hierarchy

As you might have suspected, not all courts are created equal. In fact, Article III of the United States Constitution states:

The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.

The only court that is required by the Constitution is the Supreme Court. Congress has the ability to create or dissolve lower courts.

Federal Court Structure

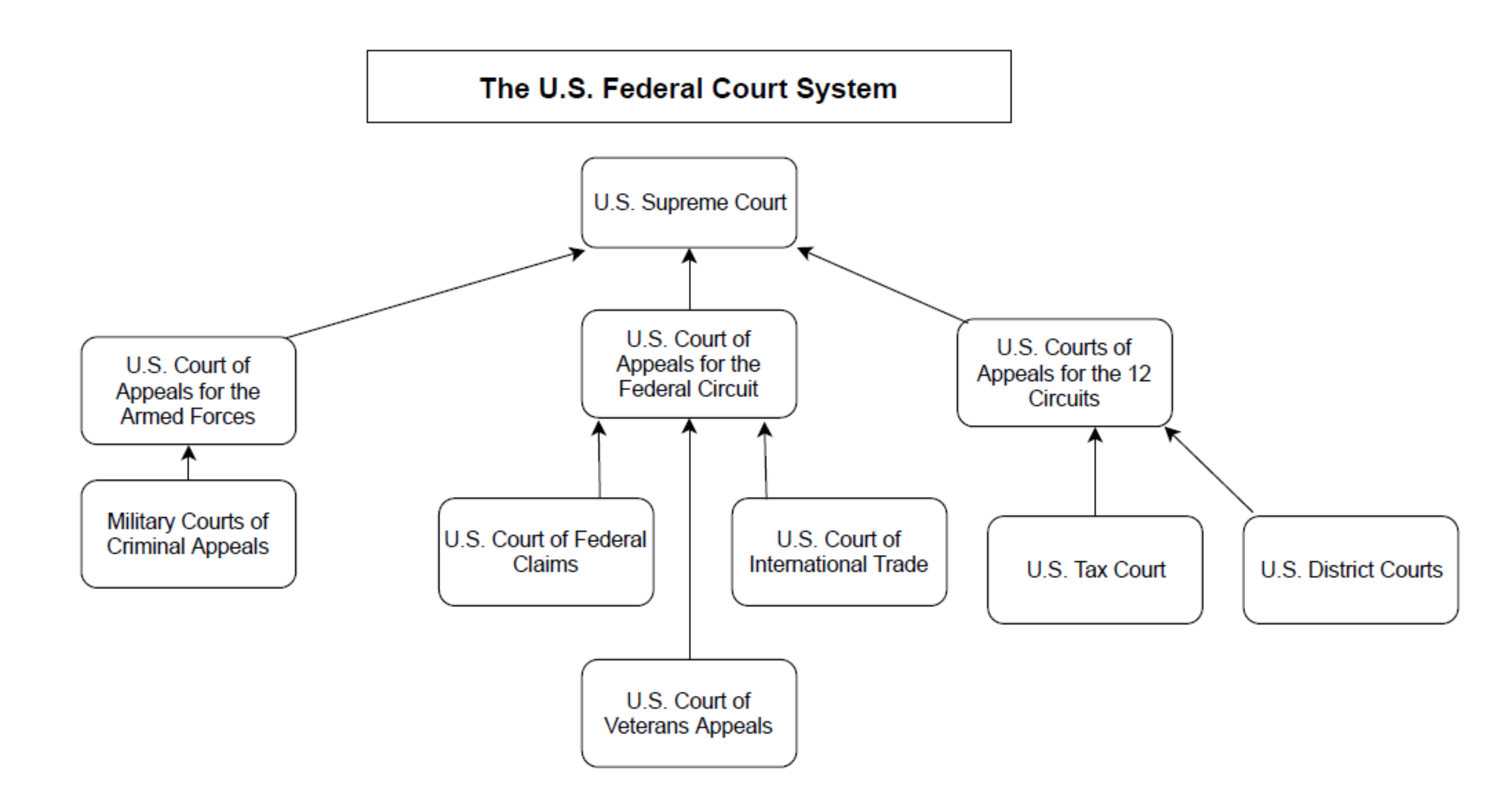

The federal court structure can be broken down in a similar fashion to a pyramid. At the top is the highest court of the land, the Supreme Court, and at the bottom are the lower level courts. In the middle are the courts which are established to handle appeals from the lowest level courts.

For the purposes of this Law-Splainer, we’ll only be discussing the federal district courts and the courts of appeals. However, it is important to acknowledge several other lower courts and those which sit above them. The United States Tax Court is another lower level court from which appeals taken are heard in the Courts of Appeals. Underneath the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit are the United States Court of International Trade, United States Court of Federal Claims and the United States Court of Veteran Appeals. Lastly, the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Coast Guard Courts of Criminal Appeals sit beneath the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. All of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals, Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces sit below the Supreme Court.

Federal District Courts

At the lowest level (for our purposes) are the Federal District Courts. There are currently 94 district courts which are broken into 12 circuits. These courts are established under 28 U.S.C. §§ 81-131. The district courts are the general trial courts of the federal system, handling both civil and criminal matters. It is also where any findings of fact and a record are established.

The number of judges that sit in each district is established by Congress in 28 U.S.C. § 133. For example, in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania there are 22 judges. Individuals who serve as federal judges are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate as required by the Constitution.

Generally, this is where most cases originate. For example, if you sought to bring a Second Amendment as-applied challenge, the federal district court is where you would start. This was the case in Miller v. Sessions, 356 F.Supp.3d 472 (2019). Likewise if you wished to sue a state government actor for violations of the Second Amendment, you would also bring suit in federal district court.

In some instances, District Courts are the first stop from appeals that start at an administrative agency. For example, when ATF revokes or denies a federal firearms license (FFL), the person or company who had their license revoked or denied may appeal the decision to ATF. A hearing is conducted by the administrative agency (ATF). If that person or company does not prevail at that hearing, they have the ability to submit a petition for review to the district court. Generally speaking, appeals to the district court are only appropriate after exhausting all available administrative remedies.

Courts of Appeals

As was the case with the district courts, the courts of appeals exist due to the will of Congress. 28 U.S.C. § 41 governs the number and composition of the circuit courts. Similarly, the number of judges assigned to each circuit are found in 28 U.S.C. § 44. Individuals who serve as a circuit court judge are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate as required by the Constitution.

There are 12 circuit courts (1st-11th Circuit and the District of Columbia Circuit). A person has an absolute right of appeal to the circuit courts, which means that if they lose at the district court, they may challenge the finding in the circuit court.

Unlike the district court, which creates findings of fact and a record, the circuit court simply reviews those findings and the record which was created below in order to determine whether the law was properly applied. Appeals are heard by a three judge panel. In some instances, either by petition of a party or sua sponte, the circuit court may hear a case en banc.

A circuit court can either affirm the findings of the lower court or reverse them. In some instances, it will remand, or send back the case to the lower court, so that it can come to a result consistent with the law.

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States is the final stop for all appeals.

Currently, there are 9 Justices (including one Chief Justice). Through the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress established that the Supreme Court would have a total of 5 justices and one chief justice (the lowest number of justices that would sit). Congress increased the number of justices to seven in 1807, nine in 1837, and then ten in 1863. This number was finally reduced to nine again in 1869, where it has remained since. As is the case with the judges in the district and circuit courts, any individual sitting on the Supreme Court is appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate as required by the Constitution.

The Supreme Court maintains original jurisdiction over “all actions or proceedings to which ambassadors, other public ministers, consuls, or vice consuls of foreign states are parties; all controversies between the United States and a State; and all actions or proceedings by a State against the citizens of another State or against aliens." What this means is that the Supreme Court has the right to initially hear all of these types of cases, but this jurisdiction is not exclusive, which means that a lower court could hear those proceedings. 28 U.S.C. § 1251 gives the Supreme Court original and exclusive jurisdiction over controversies between two or more states.

Unlike the federal courts of appeals, there is generally no automatic right of appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. A party may file a writ of certiorari asking the Court to hear its case. If the Court grants the writ (commonly referred to as “granting cert”), it will hear the case. Otherwise, if declined, the decision from the court of appeals stands. Each year, over 7,000 writs of certiorari are filed with the Court. Only about 100 are granted.

When deciding whether to grant a writ of certiorari, the Court holds a conference. If four of the nine justices vote to grant the petition, the case proceeds. The Supreme Court’s rules state that a case should be granted cert for “compelling reasons”. See Rule 10. Those reasons include:

- a United States court of appeals has entered a decision in conflict with the decision of another United States court of appeals on the same important matter; has decided an important federal question in a way that conflicts with a decision by a state court of last resort; or has so far departed from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings, or sanctioned such a departure by a lower court, as to call for an exercise of this Court’s supervisory power;

- a state court of last resort has decided an important federal question in a way that conflicts with the decision of another state court of last resort or of a United States court of appeals;

- a state court or a United States court of appeals has decided an important question of federal law that has not been, but should be, settled by this Court, or has decided an important federal question in a way that conflicts with relevant decisions of this Court.

In some instances, when a petition is denied, a justice or several justices, will file a dissenting opinion, explaining why they believed the case should be heard. However, that is the exception rather than the rule. See Silvester v. Becerra, 138 S.Ct. 945 (2018).

If the case is heard, the Supreme Court’s determination is final. However, it can, and does, remand cases to the lower courts for final adjudication consistent with its written opinion and statement of the law.

Recap

Federal courts have a hierarchy that starts at the bottom with the district courts, climbs up to the courts of appeals and ends with the Supreme Court. The district courts are the trial courts which are responsible for findings of fact and creating a record. Should a case be appealed, they go to the appropriate circuit court which reviews the lower court’s findings for errors in the application of the law. A party may file a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court if they do not prevail at the circuit court, but the Supreme Court is not required by the Constitution or the law to hear the appeal.

Next up in Part 3: Suit is Filed. What Happens Next?

Adam Kraut is an attorney and FPC's Director of Legal Strategy

Do you like this page?